TLR Advocate Summer 2023

On the Ground with the TLR Team

By Emerson Kirksey Hankamer, TLRPAC Board Member

In April, I had the opportunity to join the TLR team in Austin for a glimpse of what it takes to pass meaningful legislation to improve our state’s civil justice system.

My legislative experience to this point consisted of a college stint as a House messenger, so this experience was eye-opening.

After a staff briefing in the Austin headquarters, I joined Dick Weekley, Dick Trabulsi and others in walking the Capitol, meeting with members in offices, hallways—wherever they could spare a moment to hear our pitch.

Being back at our Capitol—this time, speaking eye-to-eye with lawmakers and observing the result of TLR’s many years of building credibility and expertise—was powerful. The respect evident in each of these meetings was striking.

Every member is busy with their own bills and the hundreds of others that flow through their committees and chambers each week. Yet in all our meetings, we had the undivided attention of the legislators, who were often literally putting down their cell phones to sit with us and listen.

This quiet dialogue is rare—particularly in a world where time is everything—and this level of respect doesn’t simply happen overnight. It’s a result of showing up, doing what you say you’re going to do, and putting in the work, year after year.

I was also struck by the professionalism of TLRs team members, each a master of their respective fields. They bring to mind this quote from Teddy Roosevelt:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

TLR is in the arena, doing the work.

There will always be those on the outside, offering thoughts and criticism, but it’s those who show up that actually make a difference. And I can confidently report that TLR is absolutely making a difference.

Texas Becomes the 31st State to Create a Specialized Business Court

By Marc Watts, TLR Board Member

When the TLR Foundation published its 2022 paper—The Case for Specialized Business Courts in Texas—29 states were operating such a court to handle complex business litigation. The hallmark of these courts is active judicial management of these complex cases by highly qualified judges.

Earlier this year, Utah became the 30th state to create a business court. And now, Texas joins the ranks as number 31.

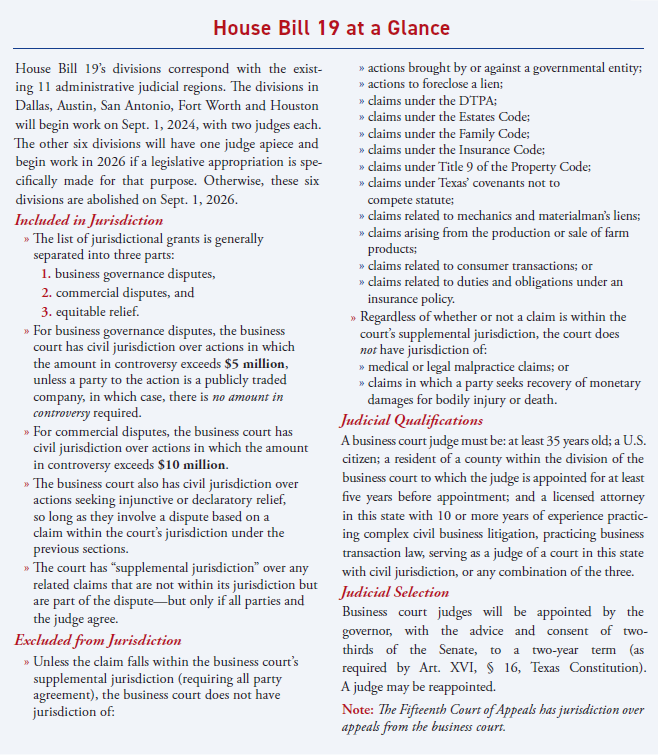

House Bill (HB) 19—by Rep. Andy Murr (R-Junction) and sponsored by Sen. Bryan Hughes (R-Mineola)—creates a specialized business trial court comprised of 11 divisions that correspond with Texas’ existing 11 administrative judicial regions. These include Divisions 1 (Dallas), 3 (Austin), 4 (San Antonio), 8 (Fort Worth), and 11 (Houston), which go into effect on Sept. 1, 2024, with two judges each. There are also six additional divisions that will have one judge apiece and will go into effect only if a legislative appropriation to provide for these divisions is made in a future session.

The court will have civil jurisdiction over business governance disputes with a defined amount in controversy, such as shareholder derivative proceedings, actions regarding the internal affairs of an organization, and actions alleging an owner breached a duty owed to an organization. The court will also have jurisdiction over actions arising from a contract or commercial transaction where the parties agreed that the business court has jurisdiction and the amount in controversy exceeds $10 million dollars (excluding interest, statutory damages, exemplary damages, penalties, attorney’s fees, and court costs). Additionally, it will handle actions seeking equitable relief, so long as they involve a dispute otherwise within the court’s jurisdiction. The court will not have jurisdiction over personal injury claims.

All of the business court judges will be appointed by the governor to two-year terms, with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. Importantly, HB 19 builds in critical judicial qualifications for these judges to ensure the court functions as intended. In addition to the qualifications required of district judges, every appointee to the business court must be a licensed Texas attorney with ten or more years’ experience practicing complex civil business litigation or business transaction law, have served as judge of a court in this state with civil jurisdiction, or any combination thereof.

A person appointed as a judge must also have been a resident for at least five years in the division to which they are being appointed, meaning local judges will oversee local cases.

Having highly qualified expert judges serving on this court will ensure these complicated and nuanced business cases are handled fairly, consistently and expediently. Under the existing system of district courts with general jurisdiction, large business cases can languish for years and can also soak up limited judicial resources that may be better used elsewhere.

Texas is home to 54 Fortune 500 company headquarters—we are the “headquarters of head-quarters,” as our friends at the Texas Association of Business often say. Our business community deserves a court system that allows them to litigate matters here, rather than in Delaware, New York or closed-door arbitration.

The effort to create a business court had enormous support this session. Gov. Greg Abbott has long advocated for such a court, even mentioning its importance in his State of the State address. Likewise, Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Hecht called for the enactment of a business trial court in his State of the Judiciary address. Additionally, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and Speaker Dade Phelan both assigned low bill numbers to the business court early in the process, making this a priority for both chambers of the Legislature.

Rep. Murr and Sen. Hughes are both highly experienced and capable legislators, who fairly and adeptly handled negotiations with interested stakeholders and were successful in shepherding this important piece of legislation efficiently through the Legislature. Their careful work improved the final product and their strong leadership was invaluable to the success of this effort.

The Texas Business Law Foundation also strongly advocated for HB 19 and its Senate counterpart. And, critically, the bill could not have made it over the finish line without strong advocacy from prominent business leaders around the state, who collectively submitted 80 letters to legislators and traveled to Austin to testify in support of the bills.

This legislation will no doubt work to streamline the resolution of business disputes and should ensure the court is staffed by qualified and skilled judges, giving our businesses confidence in Texas’ legal system and encouraging others to incorporate and establish their headquarters here in our state.

Creating Texas’ Fifteenth Court of Appeals

By Amy Befeld, TLR Assistant General Counsel

Texas has a strong preference for specialty courts.

We are one of two states with specialized high courts: the Texas Supreme Court for civil cases and the Court of Criminal Appeals for criminal cases. We have multiple specialized courts at the trial court level, including civil courts for small-, medium- and large-value cases; misdemeanor and felony criminal courts; family courts; juvenile courts; veterans’ courts; drug courts and others.

Plainly, Texans have seen the value in allowing judges to focus on a specific subject matter, resulting in judicial efficiency and consistent application of the law.

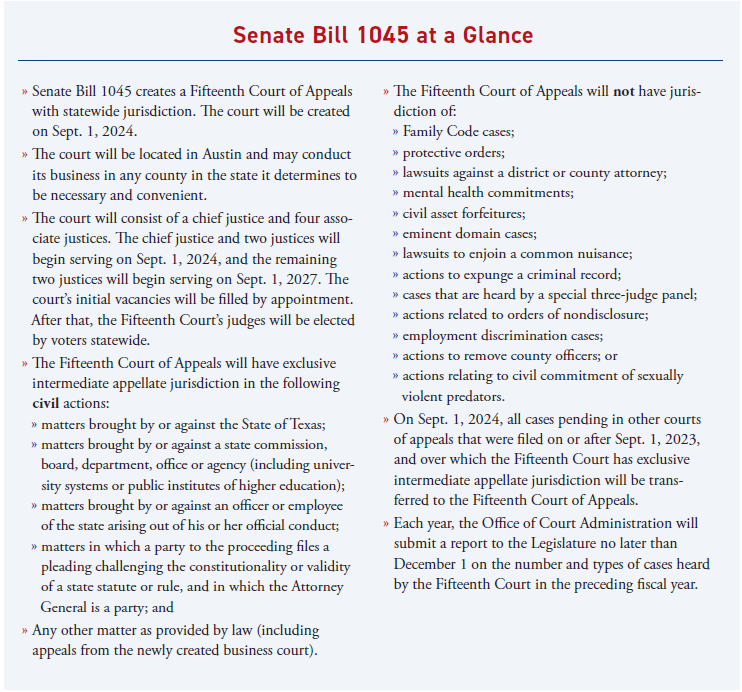

This session, the Legislature took that one step further, passing Senate Bill (SB) 1045—by Sen. Joan Huffman (R-Houston) and sponsored by Rep. Andy Murr (R-Junction)—creating the Fifteenth Court of Appeals. This court will have jurisdiction of appeals involving constitutional issues, state agencies or the state itself, and appeals from the new business trial court. Its five justices will be elected by all Texas voters.

The constitutional issues that will be heard by the Fifteenth Court are of statewide importance. So, too, are many administrative matters that will be resolved by the court. The Legislature concluded these statewide issues should be decided by a court with statewide jurisdiction, whose judges are elected by Texas voters statewide.

Currently, these important cases are being decided by regional courts, especially the Third Court of Appeals in Austin. While the Third Court hears appeals from trial courts in a 24-county area, the district’s voting population is largely concentrated in Travis County, and its judges are essentially selected by the voters of that single county.

Additionally, the Third Court is Texas’ most overworked intermediate appellate court. The Texas Supreme Court transfers cases between the 14 intermediate courts of appeals to equalize dockets. For the past seven years, the Third Court has consistently had the most cases transferred to other courts.

In Fiscal Year 2022, for example, out of the 323 cases that were transferred out of the 14 courts of appeals, 142—or nearly half—were transferred from the Third Court. Of these transferred cases, approximately 10 percent were administrative law cases, which were sent to whichever appellate court had the bandwidth to hear them. The judges receiving these administrative cases—many of which have large records and involve technical issues—may or may not have had experience with administrative law.

Many administrative law cases are hugely important, both for the litigants and thousands of Texans. They, however, are not statutorily designated as accelerated appeals. About 36 other types of cases within the Third Court’s jurisdiction are designated as accelerated appeals. This means important administrative cases may not be resolved in a timely manner.

Simply adding judges to the Third Court of Appeals will not fix this problem. However, creating a new Fifteenth Court of Appeals with limited subject matter jurisdiction will.

Additionally, the Fifteenth Court will have jurisdiction over appeals from the newly-created business court in this session’s House Bill 19. This will ensure those appeals are resolved in a timely manner. Having both a trial court and appellate court dedicated to resolving complex business disputes will provide a coherent Texas jurisprudence in commercial law and will enhance Texas’ reputation as the best state in the nation to do business.

We commend the Legislature for passing this important measure.

Leading the Charge in the 88th Legislative Session

By Mary Tipps, TLR Executive Director

Looking back over my ten legislative sessions with TLR, I’ve realized each one is like a fingerprint with its own personality and dynamics.

This session, for example, was a welcome return to normality after the COVID-19 session of 2021.

The one constant between sessions, however, is the strong leadership required to shepherd important bills through the legislative process so we can continue enacting smart policies for Texas.

Take, for example, House Bill (HB) 19, the business court bill. While TLR’s common-sense policy proposals often receive broad, bipartisan support, this bill had the added benefit of being a top priority for all of our state’s leadership.

Gov. Greg Abbott—who has long supported the creation of a Texas business court—designated it a priority in his State of the State address in February. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and Speaker Dade Phelan also gave the business court low bill numbers, giving it priority in their respective chambers. And Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Hecht discussed the benefits and efficiencies of a complex business court in his State of the Judiciary address, further signaling its importance.

This united and unequivocal support gave HB 19’s authors important bargaining power in their discussions with stakeholders. Rep. Andy Murr (R-Junction), chairman of the House General Investigating Committee, authored the bill in the House, working tirelessly to gather feedback and expertly shepherding it through committee hearings and debates. An attorney, Chairman Murr is a fair and firm negotiator with a keen understanding of HB 19’s most critical aspects, which allowed him to improve the bill while preserving its core provisions, ensuring effective implementation.

Chairman Murr was supported on the House floor by HB 19’s joint authors, Rep. Brooks Landgraf (R-Odessa), an attorney and chairman of the House Environmental Regulation Committee; Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano), an attorney and chairman of the House Judiciary and Civil Jurisprudence Committee; Rep. Morgan Meyer (R-Dallas), a business litigator and chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee; and Rep. John Lujan (R-San Antonio), a small business owner. These members were instrumental in building a strong majority to vote with Chairman Murr, fending off hostile amendments and securing bipartisan passage of HB 19.

Two Democratic members—Rep. Liz Campos and freshman Rep. Josie Garcia, both of San Antonio— courageously voted for creation of the business court despite intense pressure from the court’s opponents.

In the Senate, Sen. Bryan Hughes (R-Mineola)— the bill’s sponsor—is also an attorney, chairman of the Senate State Affairs and Jurisprudence committees, and an experienced and respected legislator. Chairman Hughes worked closely with Chairman Murr to refine HB 19 in the Senate, ensuring a strong and effective bill was ultimately passed through both chambers and sent to the governor’s desk.

HB 19 also benefited from broad support from the Texas business community, who sent dozens of letters, and called and met with legislators in support of the bill. This constituent contact was meaningful to securing passage, particularly because the business court’s opponents launched an intense campaign against it.

The Fifteenth Court of Appeals—Senate Bill 1045— was also expertly handled by its author, Sen. Joan Huffman (R-Houston), a former judge and prosecutor, chair of the Senate Finance Committee and a long-time supporter of common-sense improvements to Texas’ legal system. Chair Huffman authored a similar measure last session, and worked quickly to secure its early passage in the Senate this session. Chairman Murr sponsored this bill in the House, rounding out an important package of legislation to strengthen the efficiency, consistency and expertise of our state’s court system.

Rep. Cody Harris (R-Palestine), chairman of the House Local and Consent Calendars Committee, and Sen. Mayes Middleton (R-Galveston) adeptly handled this session’s proposed fix to abuses in the public nuisance doctrine in their respective chambers. Chairman Harris had previously filed a public nuisance bill and understands the importance of protecting the Legislature’s authority from abuses of our courts. Sen. Middleton also carried HB 4218 in the Senate—Chairman Leach’s fix to liability issues for rented trucks, which is discussed on page eight of this Advocate.

Finally, we highlight the contributions of the hundreds of professional legislative staffers who worked tirelessly throughout session on behalf of our state. These chiefs of staff, legislative directors, aides, schedulers, committee clerks, interns and others are the heart and soul of our state government. Without them, the important work of the people of Texas would grind to a halt.

We are grateful for the role all of these leaders play in keeping Texas the best state to live, work and raise a family.

Opinion: The Constitution Allows For Creating A New Statewide Appeals Court

By Scott Brister, Former Texas Supreme Court Justice

This session, the Texas Legislature created a Fifteenth Court of Appeals, with jurisdiction of civil appeals involving statewide issues. For 40 years, the 14 existing courts of appeals have done a commendable job with increasingly difficult work. I should know—I served on two of them, and for six years reviewed the work of all of them as a member of the Texas Supreme Court.

But the Legislature has not added new appellate courts or judges since 1980, while the state’s population has doubled from 14 to 30 million, and our surging economy has meant a surge in complex litigation. Each appellate justice currently disposes of about 100 opinions annually, and signs off—or dissents—on about 200 others by colleagues.

Creating the Fifteenth Court of Appeals is an effort to increase appellate consistency, funneling civil appeals involving statewide issues to one statewide court, reducing the chance of conflicts in this important area of the law.

Not everyone agreed about creating such a court, but contrary to the claims of some who opposed it, there is nothing in the Texas Constitution that bars the Legislature from doing so. Our Constitution was amended 132 years ago for this very purpose, giving the Legislature authority to create new courts of appeals, modify their districts, and expand or restrict their jurisdiction.

In 1891, the people of Texas amended both provisions of the Texas Constitution addressing the courts of appeals. Section 1 of Article V vests judicial power in the trial and appellate courts, “and in such other courts as may be provided by law.” For emphasis, it adds: “The Legislature may establish such other courts as it may deem necessary and prescribe the jurisdiction and organization thereof.”

Section 6 of the same article says the “state shall be divided into courts of appeals districts,” each with appellate jurisdiction “co-extensive with the limits of their respective districts” but “under such restrictions and regulations as may be prescribed by law.” For emphasis, our great grandparents again added that jurisdiction of the courts of appeals shall be “as may be prescribed by law.”

This emphasis on the Legislature’s power to modify the state’s judicial structure was no accident. Before 1891, several courts had held that the Constitution limited the Legislature’s power to modify the courts’ structure and jurisdiction. But after the 1891 amendments, the Texas Supreme Court in Harbison v. McMurray conceded that the jurisdiction of the courts of appeals “is not unlimited or absolute, but is subject to control by the Legislature.”

Opponents argued that the Constitution requires that the state “be divided into courts of appeals districts[.]” But divided does not necessarily mean completely separated; it often merely means “apportioned.” The Constitution requires that state government “be divided into three distinct departments,” but it does not require that appellate districts be distinct, and for nearly 60 years, two courts of appeals in Houston have had identical districts. Given the Legislature’s broad power to organize new courts and the state’s long practice of overlapping appellate districts, nothing appears to prevent the Legislature from creating a district containing all 254 counties.

Senate Bill 1045 also transfers civil appeals involving statewide issues away from other courts of appeals, primarily the court in Austin. Since it was the Legislature that originally assigned certain cases to trial and appellate courts in Austin, it cannot be unconstitutional for the Legislature to transfer them elsewhere. “What the Legislature may create, it may alter.” And by statute, the Texas Supreme Court for decades has routinely transferred appeals from one court of appeals to another.

Ultimately, the Legislature decided it was good policy to establish the Fifteenth Court of Appeals to hear matters of statewide import, a determination made with the knowledge that it had clear constitutional authority to do so.

Brister served for 11 years as a district judge in Houston, for three years on the First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeals, and for six years on the Texas Supreme Court. He is an appellate lawyer in Austin.

Additional Liability Issues on Our Radar

By Adam Blanchard, TLRPAC Board Member

This session, two bills codifying liability protections for companies in the transportation industry passed the Legislature with TLRs active support.

A number of companies—including Penske and Ryder—lease trucks to entities that use them to conduct their own business. As the lessor, these companies do not control the trucks’ drivers, routes or loads, and typically have no role in causing a collision involving a leased vehicle.

Nevertheless, plaintiff’s lawyers routinely name them as defendants, asserting the trucks should have been equipped with devices that might have prevented the collision.

These trucks are subject to extensive federal regulations and equipment requirements. And in some instances, the U.S. Department of Transportation has concluded some safety devices used for passenger automobiles may make commercial trucks less safe.

House Bill 4218—by Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano) and sponsored by Sen. Mayes Middleton (R-Galveston) —provides that truck lessors cannot be held liable for failing to equip a truck with parts or equipment not required by federal regulations at the time the truck was manufactured or sold. If, however, the lessor was contracted to maintain the truck and its failure to properly do so caused the collision, the lessor may still be sued.

House Bill 1745—by Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano) and sponsored by Sen. Robert Nichols (R-Jacksonville)— applies to rideshare companies, like Uber and Lyft, which are routinely sued in collision cases seeking to hold them vicariously liable for the rideshare driver’s conduct. The basis of the claim is that the rideshare driver is an employee of the rideshare company, despite Texas law providing that rideshare drivers are contractors, not employees.

A rideshare company may extract itself from the lawsuit through a motion for summary judgment, but not without cost. And when these companies are sued repeatedly on this invalid basis, the defense costs become substantial, resulting in a tort tax on consumers.

HB 1745 provides that a rideshare company may not be held vicariously liable for damages in a collision case when it has complied with certain statutory requirements governing its relationship with drivers, unless the claimant proves the company is grossly negligent in causing the injury by clear and convincing evidence.

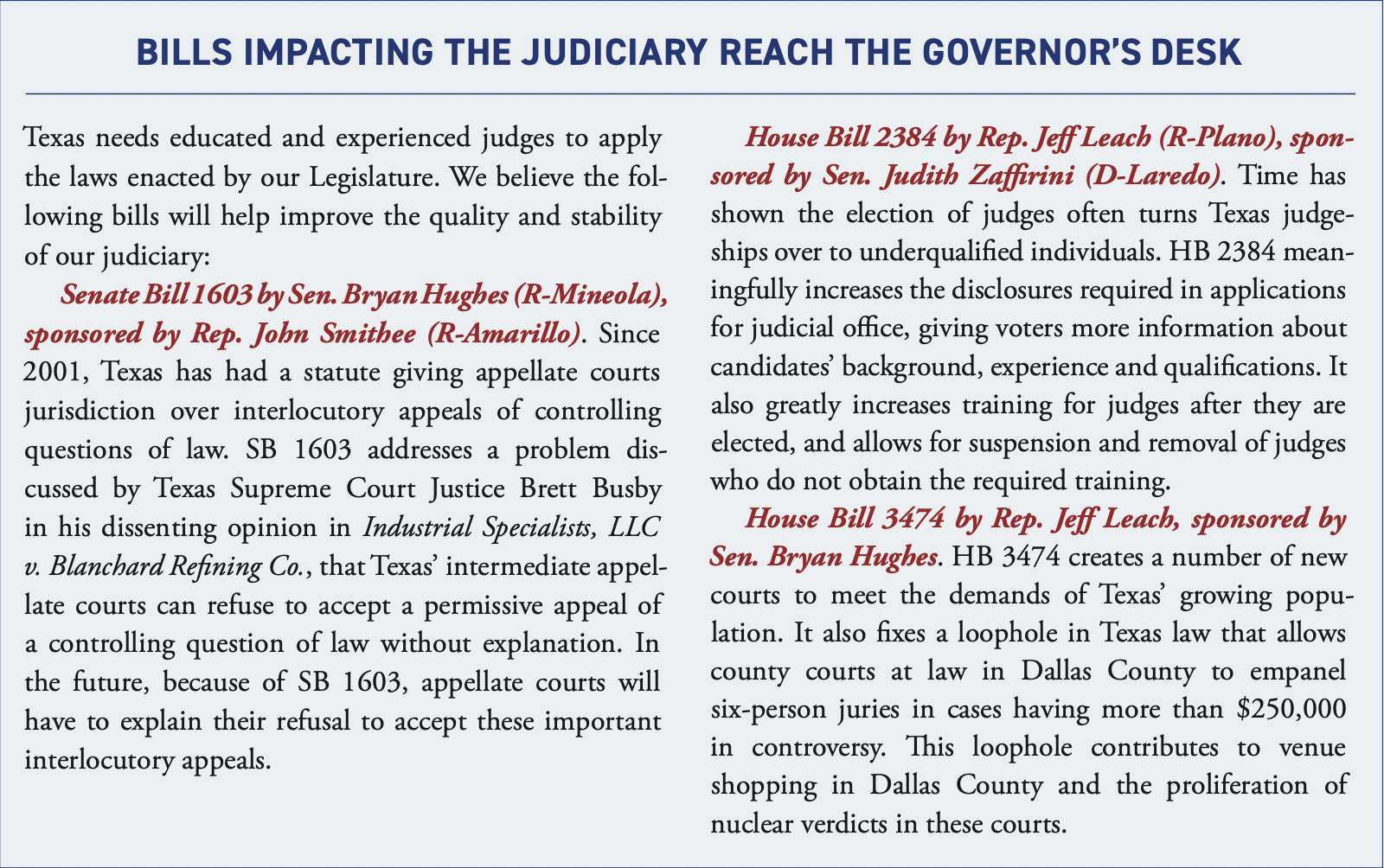

Attracting the Best and Brightest Texas Judges

By Richard W. Weekley, TLR Senior Chairman

When TLR was formed in 1994, we took a two-step approach to remedying the lawsuit abuse plaguing our state.

Step one was to help elect legislators who understood that rampant abusive litigation placed a drag on our economy and healthcare that hit the pocketbooks of every Texas family.

Step two was to advocate for common-sense legislative reforms to level the playing field, which for too long had been badly tilted in favor of personal injury trial lawyers thanks to their deep pockets and persistent lobbying.

For more than two decades, we continued to identify areas of Texas law that encouraged abusive litigation and advocated for narrow solutions to fix the identified problems, helping ensure Texans have fair and efficient courts to resolve legitimate disputes.

In recent years, it has become clear that a number of Texas judges ignore or misapply the law. These judges often impose their own view of “fairness” in the case, rather than applying the plain words of the statute or rules of evidence and procedure.

The reality of Texas’ legal environment, after nearly three decades of meaningful tort reforms, is that all of our efforts are moot if judges ignore or misapply the law, either because of incompetence, ignorance or bias.

And so, we must increase our efforts to ensure our state adds to its number of fair, competent and honest judges in our courtrooms.

This Advocate discusses bills passed this session to improve judicial candidate transparency for voters and judicial education once a judge has been elected. With over 3,000 judges serving on courts across Texas, it is critical that we continue to improve the quality and stability of our judiciary and ensure those who are elected to the bench are given the tools they need to succeed.

But there’s another, less obvious aspect of ensuring Texas has good judges—fair judicial compensation.

The Judicial Compensation Commission released a report detailing the current state of compensation in our state, finding that Texas continues to fall behind. At the district court level, our judicial salaries rank 41st among the states. We are 23rd at the intermediate appellate level and 29th at the high court level.

The base pay of a district judge (to which other judicial salaries are tied) is currently $140,000. It has not been adjusted since 2013. To compare, the base pay for judges in California and Florida is $225,074 and $182,060, respectively.

No good person enters into public service to get rich. But what incentive does an accomplished lawyer have to leave private practice to seek judicial office if a judge’s compensation is well below that of a first-year associate at a major law firm?

Texas must compensate its judges at a level that will attract good candidates for judicial office and encourage good judges to remain in office. During the 88th Regular Session, TLR supported a bill to give our judges regular pay increases without legislative action, as well as a bill providing an across-the-board pay increase. When both bills faltered, we supported legislation adding a third tier to the state’s judicial compensation structure, giving judges a pay increase after four, eight, 12 and 14 years of service. Unfortunately, that measure also failed to make it to the governor’s desk.

Our legal system cannot function without competent, fair and honest judges to uphold the rule of law. It’s time for Texas to take a hard look at what it is doing—and not doing—to attract the best legal minds to our judgeships.

We hope the Legislature will act on this next session, and if there is a special session, we hope the governor will add judicial compensation to the call.

A Departure From Common Sense

By Lee Parsley, TLR General Counsel

Since 1995, TLR has supported numerous bills that implement fair, effective and constitutional changes to Texas law.

We always seek to get it right the first time, but time and use occasionally reveal problems with how a TLR-supported statute works in the real world. When a TLR-advocated statute proves unfair or unworkable, we are the first to support amendments to improve it in subsequent legislative sessions.

This common-sense approach to dealing with legislation is, unfortunately, not universally followed. Instead, some groups that obtain changes in Texas law will oppose all efforts to reform that law, regardless of its real-world effect. This session’s attempts to modify Texas’ anti-SLAPP statute provide an example.

SLAPP is an acronym meaning Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. Take, for example, a person picketing in front of a business, upsetting the business owner and discouraging customers. The owner can sue the protester for slander, hoping the protester cannot afford to pay attorney fees and, therefore, will stop protesting. That is a SLAPP.

Because a SLAPP lawsuit infringes on the protester’s legitimate First Amendment rights, Texas’ anti-SLAPP statute allows them to file a motion to dismiss the lawsuit at the outset of the case. The judge must hear and rule on the motion quickly. In the meantime, proceedings in the case stop so the protester doesn’t have to pay attorney’s fees and can continue to exercise their First Amendment rights.

If the trial court denies the motion to dismiss, the protester may immediately appeal, during which time, all proceedings remain paused.

No one disagrees with the SLAPP statute’s intended purpose—to protect legitimate First Amendment rights. But it has a major flaw.

There is nothing stopping a lawyer from filing an anti-SLAPP motion to dismiss in any civil lawsuit—a personal injury case, a divorce, a lawsuit to enforce a covenant not to compete, an action to disbar an attorney who stole client funds, or any other kind of lawsuit.

In fact, the statute specifically names certain types of cases to which it does not apply, but that hasn’t prevented lawyers from filing anti-SLAPP motions to dismiss in those cases anyway. And so, even cases that the Legislature has specifically exempted from the SLAPP statute are being caught in a perpetual loop of motions to dismiss and appeals.

These cases can be appealed all the way to the Texas Supreme Court, while all proceedings remain frozen. And if that appeal is rejected, there is nothing stopping a defendant from starting the motion to dismiss the process over again if the plaintiff ever amends their lawsuit. This can result in years of unnecessary and inappropriate delay.

Sen. Bryan Hughes (R-Mineola) and Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano) filed companion bills, Senate Bill 896 and House Bill 2781. To limit this abusive practice in three instances: when the trial court rules the motion to dismiss was frivolous, when the motion was not timely filed, and when the anti-SLAPP statute specifically states the case is not one in which a motion to dismiss can be filed, such as personal injury and family law cases. In these three narrow instances, an immediate appeal will freeze the case for only 60 days—rather than indefinitely—during which time the defendant/ appellant can ask the appellate court to extend the stay.

In all other circumstances—when the defendant is legitimately protecting their First Amendment rights— the existing law and indefinite stay remain in place.

Unfortunately, opponents of the bills were more interested in protecting their past successes than allowing a reasonable amendment to this flawed law. They repeatedly and unapologetically mischaracterized the effect of the bills and TLRs advocacy to members of the Legislature, the media, advocacy groups and the public.

And while they succeeded in killing these two bills this session, even a casual look at the use of the anti- SLAPP statute in Texas courts clearly shows this issue will not resolve itself without legislative action in the future. While fixing this statute was not a TLR priority in this session, it will be in the next session.

The Uncured Problem of Public Nuisance Lawsuits

By Lucy Nashed Cafrelli, TLR Communications Director

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’re an attorney. But, maybe not.

Maybe, like me, you’re a fan of common-sense policies that create a robust economic environment that allows job creators and families to thrive.

Regardless, it doesn’t take a law degree—or a crystal ball—to see the threat posed by the nationwide proliferation of public nuisance lawsuits, which has been on our radar since at least 2018.

To me, it has never made sense that society would tackle major national public policy issues with piecemeal lawsuits decided by individual state courts. This web of litigation can be industry-halting, particularly for companies operating across state lines, and particularly when you consider the potential for massive, company-ending judgments.

In my opinion, the use of lawsuits to accomplish policy goals is the natural result of legislative inactivity on certain issues at the federal and state levels. Advocates on any given side of any given issue get antsy and aren’t content to see their causes languish. So, they take it upon themselves to move forward in whatever way seems most expedient.

Believe me, as a more-than-casual observer of the legislative process, I can appreciate this temptation.

But the problem is that plaintiff’s attorneys also recognize this opportunity—for a far different reason.

Take, for example, the more than two dozen public nuisance lawsuits filed by cities, counties and states seeking to hold oil and gas companies responsible for the effects of climate change.

The defendants sought to remove those cases to federal court, which is appropriate given their wide-ranging impact on national energy policy. Perplexingly, the U.S. Supreme Court recently denied this bid, sending the cases back to state courts, all but guaranteeing a convoluted mess of conflicting decisions and nuclear verdicts.

To make matters worse, the judge overseeing the city of Honolulu’s climate nuisance case—which will likely be the first-decided in the nation—recently disclosed that he presented to the Environmental Law Institute’s (ELI) Climate Judiciary Project. According to reports, ELI is connected to Sher Edling, the activist law firm created in 2017 specifically to represent “states, cities, public agencies, and businesses in high-impact, high-value environmental cases.”

The judge’s environmentalist ties are no casual coincidence, but an obvious conflict of interest with serious implications. We’ve already seen nuisance cases targeting manufacturers, tech companies and others. Even one successful climate nuisance case further fuels this fire.

So why have plaintiff’s lawyers homed in on public nuisance, specifically?

The answer, as we’ve seen time and again, is that ambiguity breeds mischief. And the public nuisance doctrine is the queen of ambiguity.

Unlike statutory nuisance, common nuisance and other types of nuisances that specifically outline their applicable actions, public nuisance is both legally vague and colloquially broad, seemingly applying to anything from waste dumping to criminal activity.

Yes, these are nuisances. But in the most technical sense of the law, they are not public nuisances. They are other types of nuisance, which are statutorily specific and leave no room for abuse. In other words, no one is creating boutique, activist law firms to go after these other nuisances.

Public nuisance’s ambiguity has catapulted it as a catch-all cause of action to regulate by litigating whatever ails us.

And it is public nuisance—not any other kind—that would have been addressed by this session’s House Bill 1372 by Rep. Cody Harris (R-Palestine) and sponsored by Sen. Mayes Middleton (R-Galveston).

This bill would have created simple guardrails to help courts determine cases the public nuisance doctrine should not apply to—namely those targeting legal or permitted activities after they have been authorized by the Legislature or a regulatory body. Unfortunately, it did not survive the legislative process.

If Gov. Abbott calls a special session this year, we suggest he add public nuisance lawsuit reform to the call. It is never too late to fix a problem.

The Unfortunate Proliferation of Causes of Action in Texas

By Richard J. Trabulsi Jr., TLR Chairman

Personal injury trial lawyers made Texas the Lawsuit Capital of the World in the 1980s and early 1990s. With a stranglehold on Texas politics, they succeeded in creating and expanding causes of action in Texas statutory law and through Texas Supreme Court opinions. Their formula was simple: more ways to sue create more lawsuits, and more lawsuits create more income for plaintiff’s lawyers.

After forming in 1994, one of TLRs first missions was to help elect candidates to legislative offices who would end the proliferation of causes of action in Texas.

To be clear, it is not that the Texas Legislature and courts should never recognize a new cause of action. Rather, it was TLR’s view then—and remains TLRs view today—that the creation of a new cause of action should be a rare exception rather than an everyday event. A time-consuming, emotionally-draining, out-come-uncertain lawsuit for damages is seldom the best solution to a perceived problem.

But Texas is at war with itself, and the creation of new causes of action is a result.

Four of the five most populous counties in Texas— representing one-third of our total population—are led by officials who are left-of-center on the political spectrum. The Texas Legislature and our state-wide elected officials, on the whole, are politically right-of-center.

As a consequence of this conflict of philosophies, the Legislature has enacted criminal statutes that local district and county attorneys sometimes choose to ignore. When local prosecutors refuse to enforce criminal laws, they strip these laws of their effectiveness. This, in turn, leads the Legislature to search for other enforcement mechanisms, which has contributed to the proliferation of bills containing new causes of action.

Recognizing the difficulty of the present situation, TLR engaged with numerous legislators this session to fashion enforcement mechanisms that achieve the Legislature’s goals without offending TLRs traditional opposition to unnecessary new causes of action.

There are multiple alternatives to lawsuits for damages. In some instances, administrative agencies are empowered to enforce laws through regulatory actions. This can include, for example, revocation of professional licenses for those who refuse to comply with Texas law.

In other circumstances, the Legislature holds the keys to enforcement of statutes because it provides funding for the affected activities. Any activity the Legislature chooses to fund, it can also choose to defund if participants refuse to comply with Texas law. And so, TLR often advocated for inclusion of these other enforcement mechanisms in bills that were considered this session.

When the author of a bill believed a civil lawsuit was the only effective enforcement mechanism, TLR advocated to the author for provisions that conform to sound tort principles. For example, multiple bills contained a waiver of Texas’ statutes governing punitive damages. TLR fought for changes to the punitive damages statutes in 1995 and 2003. Our successes have not been watered down in any prior session. We, therefore, consistently asked authors to remove the waiver provisions from their bills.

When bills contained expansive provisions related to venue and standing, we worked with the authors to amend those provisions, limiting lawsuits to persons who suffered an injury and establishing venue according to current law. When a lawsuit for damages seemed unlikely to succeed because of problems of proof or because of lengthy proceedings, we suggested the lawsuit be one for declaratory or injunctive relief, which would provide a timely and certain remedy.

In these discussions, we sought to treat each author with respect, dealing with them privately and avoiding any interference with the underlying policy being proposed. We provided statutory language each time we objected to a cause of action in a bill, and supported it with a fully researched explanation.

On the whole, TLRs entreaties were well received. Many authors changed their bills for the better. We appreciate their willingness to engage constructively with TLR.

In This Issue

- On the Ground with the TLR Team

- Texas Becomes the 31st State to Create a Specialized Business Court

- Creating Texas’ Fifteenth Court of Appeals

- Leading the Charge in the 88th Legislative Session

- Opinion: The Constitution Allows For Creating A New Statewide Appeals Court

- Additional Liability Issues on Our Radar

- Attracting the Best and Brightest Texas Judges

- A Departure From Common Sense

- The Uncured Problem of Public Nuisance Lawsuits

- The Unfortunate Proliferation of Causes of Action in Texas